genii locorum

// Site-specificity + Times of Remoteness //

ELEMENTAL OFFSET

excerpts from chapter 2

“[T]he posthumanist” point is not to blur the boundaries between human and non-human, not to cross out all distinctions and differences, and not to simply invert humanism, but rather to understand the materializing effects of particular ways of drawing boundaries between “humans” and “nonhumans”.”

- Karen Barad,

Nature’s Queer Performativity

“The boundary between physical and non-physical is very imprecise for us,” Donna Haraway writes in her 1985 essay, A Cyborg Manifesto. Exploring blurred boundaries of the physical and virtual is a mode of inquiry that I have employed throughout my artistic career, particularly apparent as an artist using display technologies as primary media, even as I have become more connected to physical location and ecosystems through my research, site-specific artworks, and lived experience.

A site-specific artwork must be contextually tethered to a location, insomuch that if it were to be extracted from the site, it would lose its relational grounding, and its meaning would be lost. Author and professor of performance studies at Exeter University Nick Kaye explains that site-specificity consists of exchanges between a “work of art and the places in which its meanings are defined.” If we discern meaning as implicitly linked to the context or situation from which an “utterance, action and event” takes place Kaye posits that we may then see the meaning of a work of art to also be implicit with place and position. In this, location becomes part of the artistic process, as something to be read within a semiotic system. “One can go on from this to argue that the location, in reading, of an image, object, or event, its positioning in relation to political, aesthetic, geographical, institutional, or other discourses, all inform what ‘it’ can be said to be.”

Kaye uses the example of Richard Serra, whose 1981 sculpture, Tilted Arc, was under threat of being removed from its location in Foley Federal Plaza in Manhattan. Serra claimed that to move Tilted Arc from its site would unequivocally destroy the work. As Kaye puts it, “To move the site-specific work is to re-place it, to make it something else.”

Swimming Upstream

In the summer of 2021, I created an augmented work in collaboration with the research collective, Belle Park Project, which includes scholar Laura Murray, documentarian Dorit Naaman and sound artist Matt Rogalsky, that drew upon the history and present day section of the Ka’tarohkwi/Cataraqui River in Kingston, Ontario. The Ka’tarohkwi is the base of the Rideau Canal and presently drains into Lake Ontario. This river was once teeming with fish, as noted by 18th-century French military engineer Pierre Pouchot while observing wildlife activity on a spring day on a mission to improve French entrenchments while England and France were at war in the 1750s: “The quantities that go up on some days is inconceivable,” as he continues to list a plethora of species undulating, jumping, and disturbing the water’s surface.

As settlers arrived in the 1780s, the river was used as a mutable channel to harness the flow and fall of the waters to generate power for mills for the production of grain and logging. The shorelines were transformed and reshaped through dams, leading to the industrialization of the river soon lined with harbours, train tracks, factories, warehouses, large wharves, and commercial fisheries. Fish species were decimated, particularly populations of whitefish and Atlantic Salmon from Lake Ontario, by these alterations further impacted by the chemical toxins and garbage industrialization produced. Biodiversity dwindled as spawning habitats were disrupted, and later by the construction of the St Lawrence Seaway power dams, hushing the busy waters of the Ka’tarohkwi.

The invitation extended to me by the Belle Project collective to create an augmented reality experience that addressed the history of the ecosystem and the surviving watershed wildlife was an opportunity that resonated conceptually and personally with me. The desire from the collective to recreate or interpret Pouchot’s account of the Cataraqui ecosystem was in part at odds with my own experience, as my initial observations of the area were an introduction to a wider range of nature than I had ever witnessed in my lifetime, yet, I was commissioned to make work about a dwindling ecosystem.

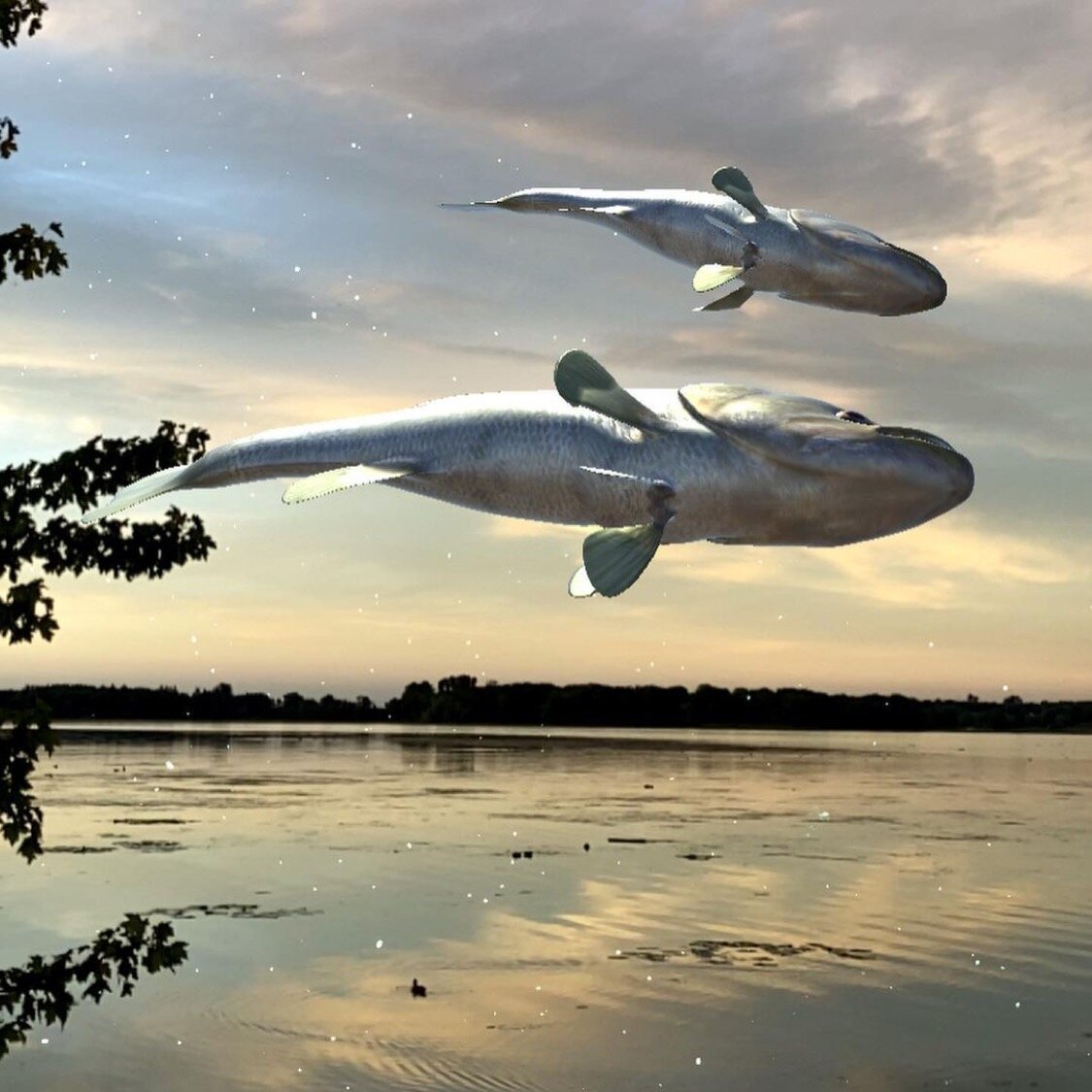

I created a 3-dimensional animated vista featuring prominent fish species that lived in a narrowly specific portion of the river. In this area, the water’s current was calm and relatively still, ideal for minnows, the American Eel, Rounded Gobi, Largemouth Bass, and Pumpkin Seed Fish. I sourced 3D scans of these species with 4K photographic image textures (the skin of the models) made available via the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University and integrated them into a scene that was accessible via the App Store, which can be accessed by clicking here.

Once the free standalone App I created was downloaded via a QR code, a fiducial marker (an image to which viewers aim the camera of their mobile devices) allowed visitors to view and move around accurate anatomical animated models of the species that lived and continue to live within a narrowly precise area of the Inner Harbour. Rather than creating the illusion that the fish were swimming in the water, the fish swam above the horizon, as though extending the river’s population into the air. Binaural audio recorded with submersible microphones by Matt Rogalsky featured the sounds feet below the exact location where the fiducial marker could be found in the inner harbour. This offset of sound and image brought the ecosystem just outside of our perception beneath the surface of the water, into prominence during the mediated experience of the app.

Throughout the summer, engagements with the public and communities invested in water health and biodiversity took place. PhD Biology student Wenxi Feng, studying at Queen’s University, visited Swimming Upstream and offered viewers the additional perspective of looking beneath the water with a submersible drone. Almost immediately, through the large tendrils of plants and fog of silt, the species featured in the augmented reality (AR) emerged from the darkness and were seen remotely on the handheld LCD console of the drone controls.

To view, download Swimming Upstream from the App Store, open the app and aim your device's camera at the symbol above.

Remotely Close - Eros’s Kiss

The superimposition that Swimming Upstream effectuates within a specific location was a marked difference for me from the augmented reality work that I had created in response to COVID restrictions in the previous year, at the height of the pandemic. Eros’s Kiss (2020) was an AR experience commissioned by Art Toronto, which invited would-be visitors of the art fair to bring my anthropomorphic roses into their homes, gardens, or wherever they wished. Eros Kiss’ continues upon a series of AR works that I made to contemplate interspecies communication, drawing upon the allure of the blossom as the reproductive structure of the plant to attract pollinators, how information is transferred between plants, and how humans cultivate plant morphology. Eros’ Kiss featured two roses of the same plant, embraced in an act of tender self-pollination, pressing their delicate petals into one another, deeply kissing, again and again. As roses encompass male and female organs in each flower, they are capable of self-pollinating, producing seeds that germinate into what many gardeners deem as underwhelming rose plants with smaller, less exuberant blossoms. Gardeners will often remove the rose's anthers when the rose is a bud. Shielded under a covering, such as a paper bag, the developing stigma is allowed to mature slowly, whereupon the plant will be manually cross-pollinated with another rose plant to create a new rose hybrid. The embrace of the rose in Eros’ Kiss is with its mirror self, protected within a glass vitrine to enjoy the freedom of autonomy and unmediated self-pollination. The apps act as sculptural GIFs, cyclically engaging in simple interactions.

Thousands of people accessed Eros’ Kiss, and shared screen recordings of the flowers kissing in their kitchens and studies, backyards and bedrooms. It was a way for the art fair to feature spatial work, albeit digital, to patrons in a time when the fair was online, limiting artworks to a two-dimensional viewing experience. What I found striking was the intimacy that emerged from the public sharing their private spaces publicly online, sharing a tender moment with my roses in sites of familiarity. In a sense, it became an iterative, public-generated engagement in site(s)-specificity.

Swimming Upstream and Eros’ Kiss were stepping stones towards a broader exploration of form (both physical and non-physical), remoteness, and engagement with site-specificity. In the preceding chapters, I will detail four works that represent the culmination of my research-creation practice over the course of my graduate degree. Each work employs the methodology of the offset to render the invisible visible, aural, or felt.